Henri Matisse was 60 the first time he came to New York, passing through on his way to Tahiti, where he hoped a different kind of light would jolt him out of a vexing slump; he hadn’t finished a painting in two years.

Arriving at nightfall, gliding up the Hudson River, he was captivated by the skyline reflecting black and gold in the water, like a “sequined dress.” If he had come to New York as a young man, he later told an interviewer, he never would have left.

In his studio in Paris, on another river, Matisse made his early breakthrough experiments, including the View of Nôtre Dame, now in MoMA’s permanent collection.

How his painting might have developed if the Hudson River and Manhattan skyscrapers had been the setting for his radicalism, rather than the 500-year-old cathedral is worth giving more thought on November 25, when Elaine Sciolino, NYT Paris bureau chief discusses her book The Seine, the River that Made Paris.

The first time Matisse saw the paintings of Paul Cezanne, he said to himself “If Cezanne is right, I am right.”

If without Cezanne, there would have been no Matisse, without Gustave Courbet, there would have been no Cezanne. Courbet’s socialism brought him to reject romantic idealism, painting women, workers and scenes of daily life with a candor that was criticized in terms similar to those applied to the contemporaneous newfangled velocipede, as a matter of “putting the cart before the horse.”

On November 12, the Making of a Masterpiece series of talks at the Metropolitan Museum of Art kicks off with a discussion of Courbet’s Woman with a Parrot.

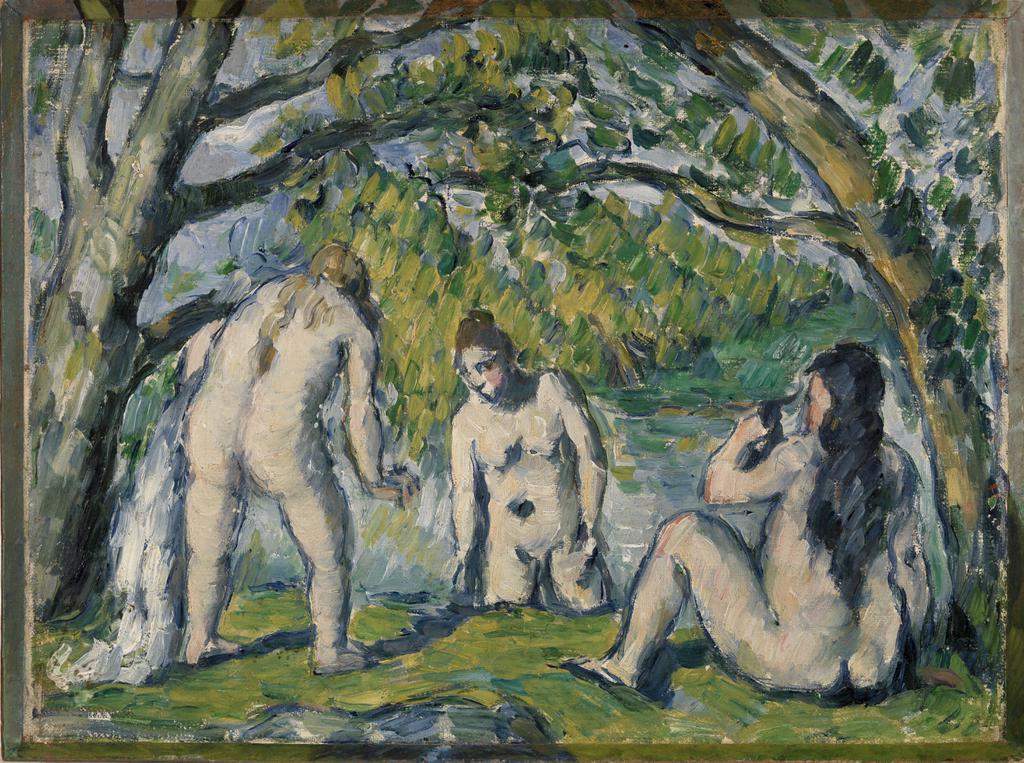

Like all artists, Matisse was a collector, buying paintings even when he was broke. To get the $100 needed to buy Cezanne’s Three Bathers, he pawned an emerald ring, a wedding gift to his wife. Thirty-seven years later, when he donated the painting to the city of Paris for its museum, he said, “…it has supported me morally at critical moments in my venture as an artist; I have drawn from it my faith and my perseverance.”

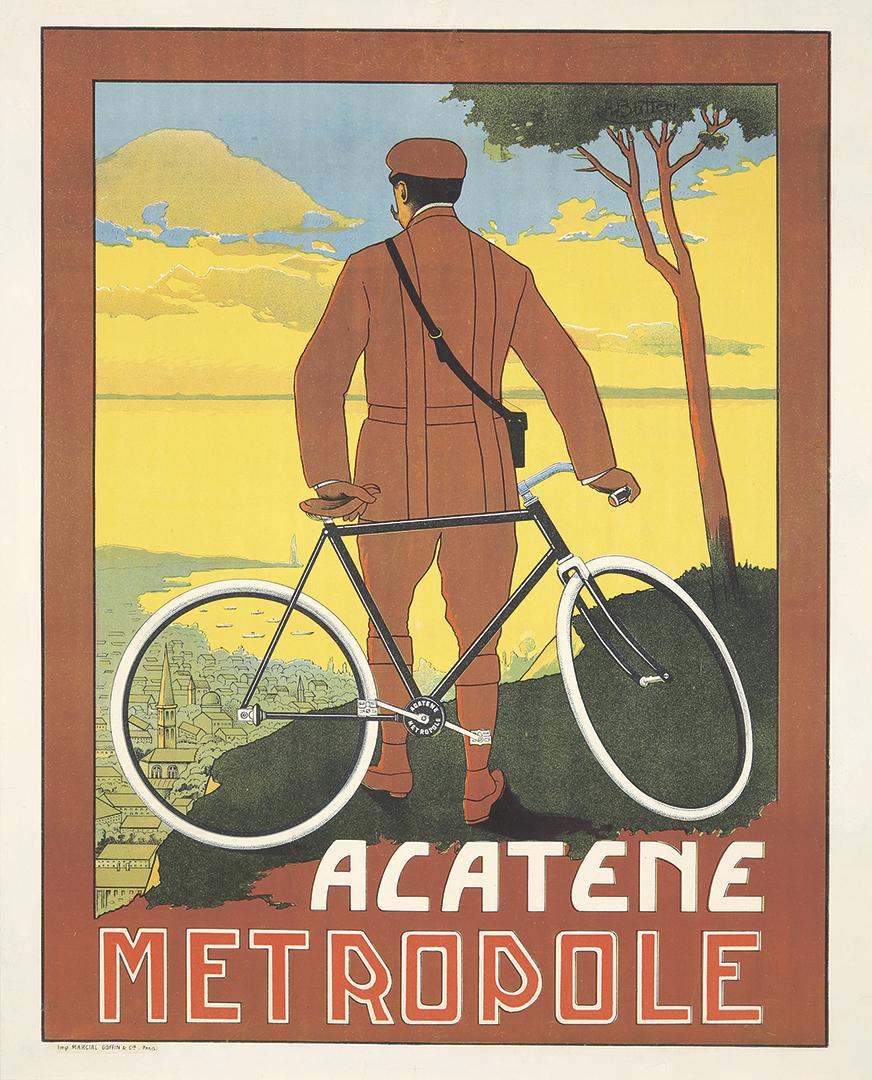

He always regretted not having had the money to buy Van Gogh’s Arlesienne, when the price was about the same as a good bicycle. He asked his brother Auguste to lend him the funds. The brother opted to buy the bicycle instead.

If your preferences tend more toward Auguste’s, the Five Borough Bike Club has got you covered on November 23 with a Brunch n’ Hike ride in Monmouth County. The ride follows the shoreline for a bit, includes a walk in the woods and begins and ends with snacks. As the name suggests, this is a social ride accessible for every level of cyclist, so if your passions are more like Henri’s, check it out.

November is a great time to ride, but it can be chilly. Gloves and socks! Gloves and socks! It can never be said enough: there is no such thing as bad weather, only bad outfits. If you’re short on equipment for winter riding, head over to Mr. C’s Cycles in Sunset Park for 15% off on all clothing.

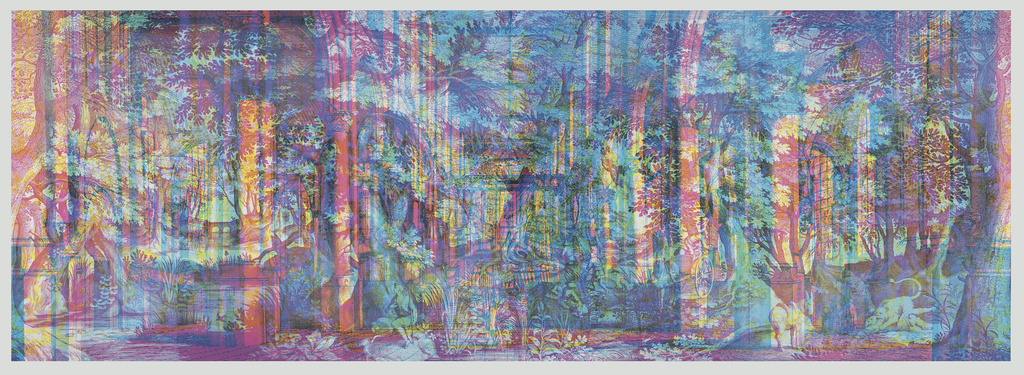

Matisse didn’t find what he was looking for in Tahiti; he lacked Gauguin’s “combativeness,” he said, to counteract an ambiance he described as both “superb, and boring.” It was the “crystalline quality” of the New York light that excited him. When he got back to France, he began cutting out pieces of painted paper to plan his paintings, “drawing with scissors,” which led to a new period of experimentation, redefining what painting could be yet again, radical to the end.

But not too quickly, if you know what I mean, or you will miss out on the pleasing crunch of the dry leaves on the pathways of Central Park beneath your wheels, signaling that the surrounding green has reached its ultimate fullness, and will soon be turning to red.

But not too quickly, if you know what I mean, or you will miss out on the pleasing crunch of the dry leaves on the pathways of Central Park beneath your wheels, signaling that the surrounding green has reached its ultimate fullness, and will soon be turning to red. Architecture has been famously called frozen music; on Thursday nights throughout September, both the frozen and liquid versions can be experienced simultaneously when Jazz at Lincoln Center brings New York City’s

Architecture has been famously called frozen music; on Thursday nights throughout September, both the frozen and liquid versions can be experienced simultaneously when Jazz at Lincoln Center brings New York City’s  And where better to enjoy a refreshing bike ride than Staten Island, New York City’s greenest borough?

And where better to enjoy a refreshing bike ride than Staten Island, New York City’s greenest borough?